|

The Preston Guardian, Saturday, 26th

September, 1863

STEAM PLOUGHING IN THE

FYLDE.

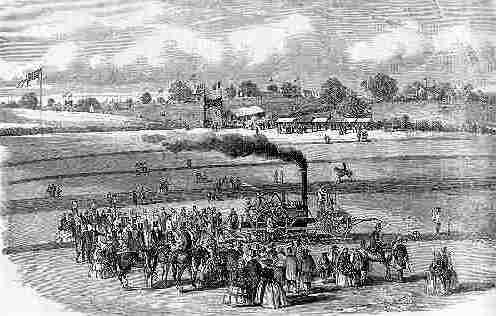

On

Thursday last, an experiment of an interesting character was tried on the Preese

Hall farm. One of the fields was announced to be ploughed on that day by the agency

of steam power, and as the event had been pretty widely advertised, there was a

great gathering of farmers and others to witness the performance. There were people

present from all parts of the Fylde, and as the railway company had promised that

they would stop the trains at the Todderstaff crossing, about half a mile from the

trial field, many gentlemen from Preston were induced to visit the scene of

action.

Altogether many hundreds were in the field. The machine was

Fowler's patented steam plough. The steam engine and the plough arrived by

rail, on Monday evening, but they could not be unloaded at the Kirkham station, so

they were taken on to Lytham.

On

Tuesday evening they left Lytham for Preese Hall, a distance of about nine miles,

by the highway, and the novel circumstance of a steam engine perambulating the

roads, and dragging after it a truck, on which was the plough, itself a most

curious piece of mechanism, attracted a great deal of attention along the route,

and large numbers of wonder-stricken beholders followed the first steam carriage

that ever traversed the highways of the Fylde, to its

destination.

On

Thursday morning it was at work in one of the fields, and for several hours it

turned up the soil, to the satisfaction and astonishment of the crowds in

attendance. It was, in fact, a great success.

Preese Hall farm, in the township of Weeton-with-Preese, is a

portion of the estate purchased by Thomas Miller, Esq., of Preston, about ten years

since, from the trustees of the late Mr. Hornby, of Ribby. Like the Singleton,

Hardhorn, and other property of Mr. Miller, in the Fylde, it has been so changed by

the judicious and enterprising course of improvement which that gentleman and his

agent, Mr. Fair, of Lytham, have carried on, that anyone who had inspected the farm

before it came into Mr, Miller's possession would certainly not now recognise it.

It belongs essentially to that portion of the Fylde whose improvement received the

commendation of Lord Stanley, at the North Lancashire Agricultural meeting; at

Lancaster, this year.

It

was with the view of testing the merits of steam ploughing that Mr. Fair, on Mr.

Miller's behalf, arranged with Messrs. Fowler, of Leeds, patentees and

manufacturers of steam ploughs and other agricultural machinery, to have a trial of

their plough on Preese Hall farm, and it was in a field of thirty acres that the

machinery was fixed.

At

the top of' the field, the “headlands," as ploughmen call it, a steam engine,

nominally of fourteen, but capable of working to forty-five, horse power, was

fixed. It is a portable one, on four broad wheels, so that it can be easily moved

along the field, or from one field to another, at the will of the person in charge.

At the opposite end of the field is " an anchor," round which and round a patent

windlass in connection with the engine, an "endless" wire rope revolves, of the

required length ; and on this ropes, between the engine and the anchor, the plough,

or whatever other machine is used, is moved along.

The

windlass, or drum, is composed of a number of small levers that grip the rope, and

thus prevent its slipping—an ingenious invention that has been advantageously

applied, with a view to prevent accidents, in colliery haulage. The plough is what

may be called a "balance' or double one; that is, the two ends are

alike.

The

one used on Thursday had four "shares" or coulters at each end, so that there was

no occasion for turning it at the completion of a furrow. One end of the plough is

thus always in the air, and they are alternately at work and at rest. The change is

effected in about a minute.

The

field in which the ploughing took place is a strong loam soil; it was pasture last

year, and it is to be sown, after ploughing, with oats. The length of the furrows

was about 250 yards; the plough with its four coulters, at each journey turned up 3

feet 8 inches in width of soil, or in the double journey 7 feet 4inches wide,

altogether an area of 611 square yards. It took just over three minutes to complete

one length, or allowing a minute at each end of the furrow for changing the plough,

eight minutes and a half for the out and return " trip." This makes a few minutes

over the hour for a statute acre, which is considered a good day's work for a pair

of horses. The steam plough, however, makes a deeper furrow than is usually

attempted by horse ploughing ; five or six inches being considered a fair average

for the latter while this does seven or eight. It also lays the furrow quite as

well as the horse ploughing.

After

having shown the ploughing, Mr. Greig, of the firm of Messrs. Fowler, the

patentees, attached to the engine a digger, of five coulters. With this, which is

on the same principle as the plough, but has five coulters instead of four, and

which are narrower and go considerably deeper, the furrows were done in less time,

Mr. Grieg stating that twelve acres a day could be easily done.

As

the digger was driven along, the soil was thrown up like surging waves, and a large

stratum of subsoil was thus brought within the action of the atmosphere. A

cultivator was on the ground, but some portion of the connecting machinery not

having arrived, it was not tried. Harrowing could also be easily done by steam on

the same principle.

About

half-past two o'clock a fearful storm of thunder, lightning, and rain set in and

continued some time. Mr. Greig, therefore, stepped the working of the machinery,

for the crowd were only too glad to leave the spot and seek shelter in the

refreshment tents in the field, one of which was kept by Mr. W. Carter, of the Ship

Inn, Lytham, and the other by Mr. Redman, of the Miller's Arms, Singleton. In the

former tent an excellent collation was served to a number of invited guests. He had

when he finished work ploughed about six acres.

As

respects ploughing by steam, its advantages or otherwise is a mere matter of

calculation. On very large farms there can be little doubt there will be economy in

its use, and should this be found to be the case, there will probably be, as

suggested by Lord Stanley, at the Lancaster agricultural meeting, the principle of

co-operation brought to bear to allow of steam being used by smaller farmers also.

This principle has already been acted upon in many parts of Lancashire in the case

of rearing machines, and no doubt steam machinery in the field will be similarly

obtained.

We

understand that Mr. Fair has arranged for the purchase of one of these machines for

Mr. Miller, and its practicability will thus shortly be further tasted. The cost of

a steam engine, with plough and all appliances, is, we understand, about £800. To

work it there requires a man at the engine, one at the plough, a boy at the anchor,

and two boys to attend to the hearers, which support the rope between the engine

and the anchor, and to remove them from under the rope as the plough approaches,

and replace them when the plough has passed. The bearers are placed along the field

at intervals of forty yards, to keep the rope off the ground. The bearers on the

outer length of the rope are self-acting, and need no attendance.

There

is fuel, &c. to be added to the expense of working; altogether &c.,

estimated cost of the working is about £2 a day. One great benefit of steam

machinery is, that work being done more quickly, advantage can be taken of

favourable weather and other circumstances to have farming operations completed at

the most suitable period. The introduction of steam must follow other improvements,

for to work steam machinery to advantage there must be large fields, straight

fences, and land must he well drained, all being conditions desirable in themselves

but absolutely essential for the profitable employment of this kind of

machinery.

The

introduction of the steam plough into the Fylde is an important event in its

annals, and it is somewhat significant that the farmers are indebted to it to one

of the modern race of landowners, one who has invested in land the wealth earned in

commercial pursuits, the " new blood" in the landed aristocracy that has done so

much for the improvement of agriculture, and bringing it up, in the march of

improvement, with the other creators of national wealth—commerce and

manufactures.

|